The Ecosystem Behind De-banking in Canada

Why Muslim-led and humanitarian charities are being shut out of the financial system — and who’s responsible.

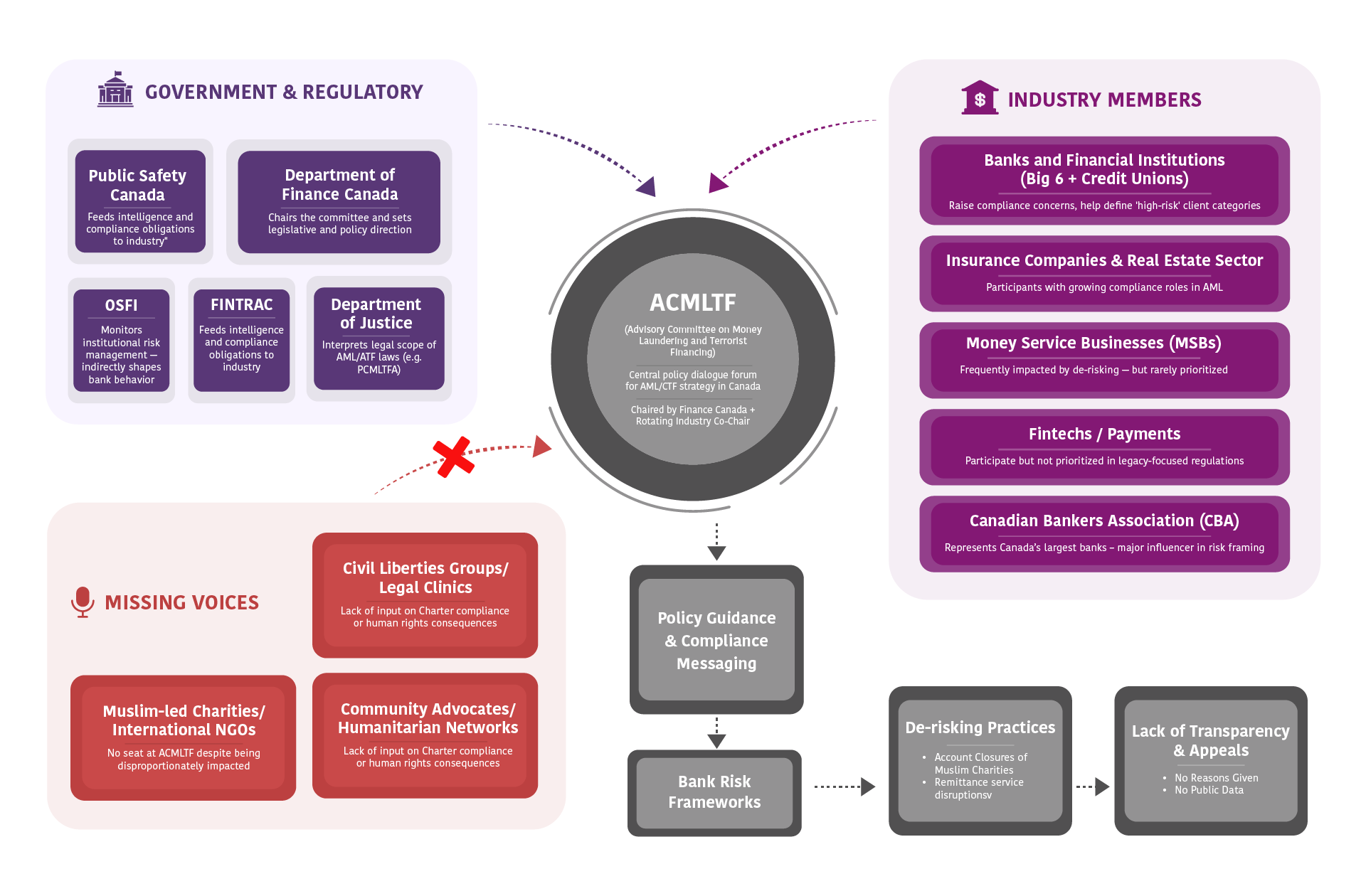

The Policy Ecosystem and Its Disproportionate Impact on Muslim Charities

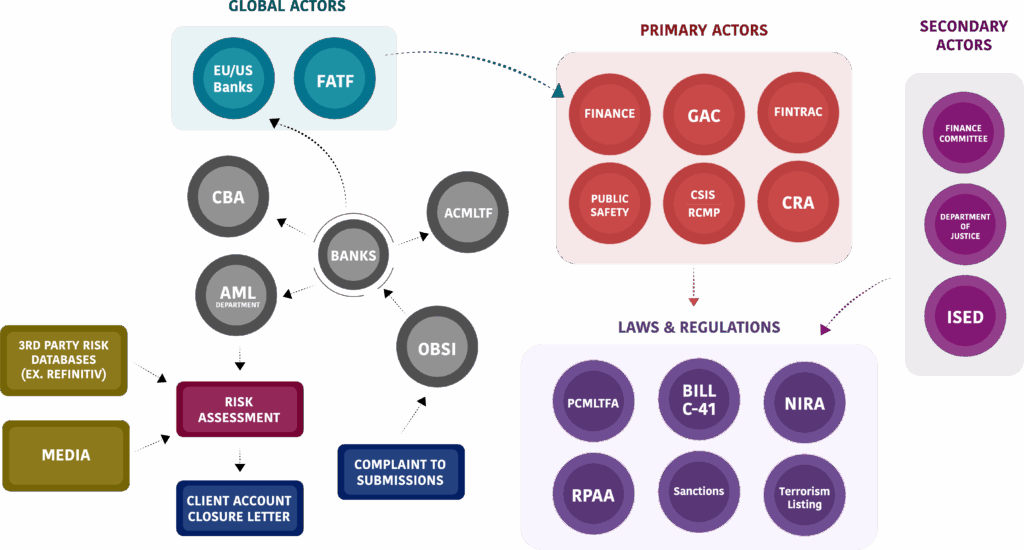

De-banking isn’t caused by a single law or agency. It’s the result of a complex ecosystem where banks, regulators, intelligence agencies, and government departments interact — Muslim-led and humanitarian charities are disproportionately caught in this web. Here’s how the system works, who the key players are, and why change is urgently needed.

The De-Risking Framework

Government Players

- Department of Finance Canada

-

- Writes Canada’s anti-money laundering law: the PCMLTFA.

- Promotes a “risk-based approach,” but its focus on terrorism financing has made banks overly cautious.

- Its own risk assessments label Muslim-led and humanitarian charities as high risk — setting the tone for the entire system.

- In 2023, it acknowledged de-risking as a concern and launched consultations.

- Finance Canada’s Advisory Committee on AML/ATF (ACMLTF)

-

- Brings banks, regulators, and law enforcement together to shape AML/ATF policies.

- Civil society has no seat — affected charities are excluded from the table.

- Without diverse voices, risk policies lean toward caution, not inclusion.

- House of Commons Finance Committee (FINA)

-

- Oversees AML/ATF legislation and banking access.

- Raised alarms as early as 2015 about overreach and biased data collection.

- Can’t force change, but its public findings and recommendations shape national debates.

- Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI)

-

- Regulates Canada’s banks and how they manage risk.

- Tells banks to assess risk — but doesn’t stop them from overcorrecting by exiting entire sectors.

- Its high compliance expectations create pressure to drop high-risk clients, even without wrongdoing.

- RCMP & CSIS

-

- Feed banks intelligence alerts and risk indicators — even without charges or listings.

- Banks react swiftly to this “pre-criminal” information.

- Case example: IRFAN-Canada was de-banked years before being officially listed as a terrorist entity.

- FINTRAC – Financial Intelligence Unit

-

- Collects and analyzes reports from banks.

- Its strict rules and penalties create a “zero-tolerance” culture.

- Warns against blanket de-risking — but banks often overreact out of fear.

- Banks interpret ethnicity, religion, or geography as proxies for risk, contributing to profiling.

- Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) – Charities Directorate & RAD

-

- Audits charities for possible terror financing.

- 85% of charities audited and revoked under RAD were Muslim-led and humanitarian charities.

- CRA’s red flags ripple across agencies and banks, even when no wrongdoing is found.

- Risk information spreads — but exoneration rarely does.

- Department of Justice Canada

-

- Crafts legal interpretations of anti-terror laws.

- Broad definitions (e.g. pre-C-41 law) created legal risks for legitimate aid.

- Has the power to clarify that discriminatory de-risking violates Charter rights.

- Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC)

-

- Protects individual consumers — not organizations.

- Can’t force a bank to explain or reverse account closures.

- Doesn’t collect public data on who’s being de-banked — major accountability gap.

- Innovation, Science & Economic Development Canada (ISED)

-

- Oversees nonprofit transparency and corporate registries.

- Better data sharing from ISED could reduce banks’ uncertainty about charities.

- Supports fintechs — but banks still hold the final power to cut ties.

- Global Affairs Canada (GAC)

-

- Administers sanctions and humanitarian exemptions.

- Can issue permits under Bill C-41 for charities operating in conflict zones.

- Tries to keep aid channels open — but banks often ignore or sidestep its exemptions.

Legal and Regulatory

- PCMLTFA (Proceeds of Crime and Terrorist Financing Act)

-

- Canada’s main AML/ATF law.

- Enforces a risk-based approach — but vague guidance leads banks to err on the side of caution.

- Revisions in 2008 sharply expanded penalties and scrutiny, triggering sector-wide de-risking.

- FATF Recommendation 8

-

- International standard labeling nonprofits as vulnerable to terror financing.

- “Soft law” — but enforced domestically as if it were binding.

- Canada’s interpretation is harsher than other G7 countries.

- Result: Muslim-led and humanitarian charities face stricter audits and banking restrictions.

- National Inherent Risk Assessments (2015 & 2023)

-

- Government reports that labeled charities as “high-risk” without accounting for controls.

- Banks use these labels to justify account closures.

- Ignores residual risk — the actual risk after oversight, compliance, and controls are applied.

- Bill C-41 (2023) – Humanitarian Exemption Reform

-

- Created legal paths for charities to work in terrorist-controlled areas.

- Provides automatic exemptions for life-saving aid, and permits for development work.

- Still leaves grey zones — banks often stay cautious, blocking wire transfers anyway.

- Bank Act & Retail Payment Activities Act (RPAA)

-

- The Bank Act guarantees personal banking rights — but not for organizations.

- RPAA regulates fintechs — but doesn’t require banks to serve them.

- Both laws give banks wide leeway to cut ties based on risk appetite.

- ACCS Report #4 – Inherent vs Residual Risk

-

- Recommends shifting Canada’s risk model to reflect real, mitigated risks.

- Highlights that compliance and audits reduce actual risk — and policy should reflect that.

- Aligns with global best practices and FATF’s updated position.

Banking Sector’s Role

- Canadian Bankers Association (CBA)

-

- Represents Canada’s major banks.

- Advocates for risk-sharing and clearer regulations — but doesn’t oppose de-risking.

- Defends banks’ discretion to exit clients based on internal policies.

- Ombudsman for Banking Services and Investments (OBSI)

-

- Handles banking disputes — but can’t reverse account closures.

- Offers little recourse for de-risking victims beyond delay or notice extensions.

- Recommends affected individuals pursue human rights complaints.

- AML/CFT Departments in Banks

-

- These internal teams manage risk based on compliance, not inclusion.

- Incentivized to avoid risk at all costs — even if that means dropping legitimate clients.

- Often staffed by ex-law enforcement or security professionals who act conservatively.

- Use secretive algorithms, internal scoring, and third-party data (e.g. World-Check) to flag clients.

A System That Protects Itself — But at What Cost?

De-banking is not accidental — it’s the outcome of a system optimized for risk avoidance, not fairness. Muslim-led and humanitarian charities — particularly those doing humanitarian work in conflict zones — bear the brunt of this design.

Know Your Rights